- I consulted a lawyer, this piece of paper means nothing, says Olga Pavlova.

Before the release all female prisoners of cell #18 were forced to sign a statement that they would never take part in protests and would not disclose the details of their prison stay. An unknown man in civilian clothes lectured the women and threatened that those who break this promise would be charged with a criminal offence and get a long prison term this time.

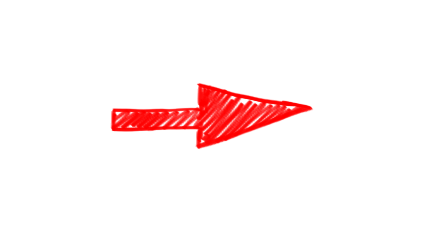

These educational lectures were absurd. One by one women were taken into a room. There was a mirror against the door, and they were told to look right in it. An unknown man sat in the far corner behind them. The women had to look into the mirror as they talked to the man but they were forbidden to look at him. All this seemed ridiculously funny because it is funny when a person who cannot write a protocol without making grammar mistakes is trying to use the methods of psychological conditioning and neurolinguistic programming. But maybe the women were laughing because they were in a good mood, and the mood was good because it was clear: they were not going to get killed, they were going to be let go.

Olesya S. openly made funny faces. She twirled in front of the mirror exclaiming “Oh wow! I lost some weight here on your diet, that’s so cool!” Olesya says that this mysterious neurolinguistic programmer pouted like a big child after he realized that he was just as bad at psychological programming as at spelling. Other prisoners signed. Or refused to sign. The mystery man even showed Nastya B. a criminal case that was supposedly opened on her in Soligorsk in 2015, five years before these events. This was the first time she heard about it.

After these educational conversations and signatures, the women were told that they were being let go and… taken right back into the cell and held there for half a day longer. There they seriously discussed how binding this promise to stop participating in protests and the non-disclosure agreement were and whether they imposed any legal obligations on them. They decided they did not. All came to an agreement that in cases of continued participation in protests these affidavits could not be used to open criminal cases against them. It is amazing how liberation, not even actual, but merely looming on the horizon, returned the nearly lost belief in the existence of law on the territory of Belarus to the inmates of cell #18.

Why wouldn’t they open a criminal case on the grounds of this paper they signed, if Nastya B. just saw a criminal case opened against her for no reason whatsoever? If they initiated an administrative case against every single one of the 36 women on the grounds of copy-pasted and completely false reports, why couldn’t they open a criminal case on the grounds of a candy wrapper if they wanted to?

This is what an outside observer and listener of their stories thinks. But the sheer fact of discussing the affidavit shows that the inmates of cell #18 assumed that lawlessness was just about to end, that the violated laws would somehow work again, that justice would triumph, even though it never triumphed once in their case.

Perhaps they just wanted to believe in goodness because they felt it in the air: they were not going to get killed, they were going to be let go. And it never occurred to anyone to question this release. Why were they releasing them before their jail term was over? Did the system get clogged? Did it chocke on the humans it swallowed? Or was it freeing up some space for those who would serve not days, but years this time?

Catacombs

The women are taken out of the cell and told to face the wall. Even walking towards freedom they still have to face the wall, still march in line with hands behind their backs, still look only at the floor. Though some liberties are not noticed. Hanna L., for example, is led by the arms. Her glasses had been confiscated, and Hanna can hardly see anything on the poorly lit staircases.

They are not taken to the exit but to the basement corridors. The inmates do not think that they are being led to an execution because this time it is obvious, they are going to search for their belongings that were confiscated during the intake.

Basement corridors and rooms are littered with things, how can anyone find anything around here? Sweaters, jackets, belts, glasses, necklaces, watches, passports, telephones. A couple of phones still buzz. “Where are you? Text me back!” someone is still trying to reach a lost relative. On the day of mass arrests confiscated phones sang like a chorus. Few of them survived till release day, batteries died.

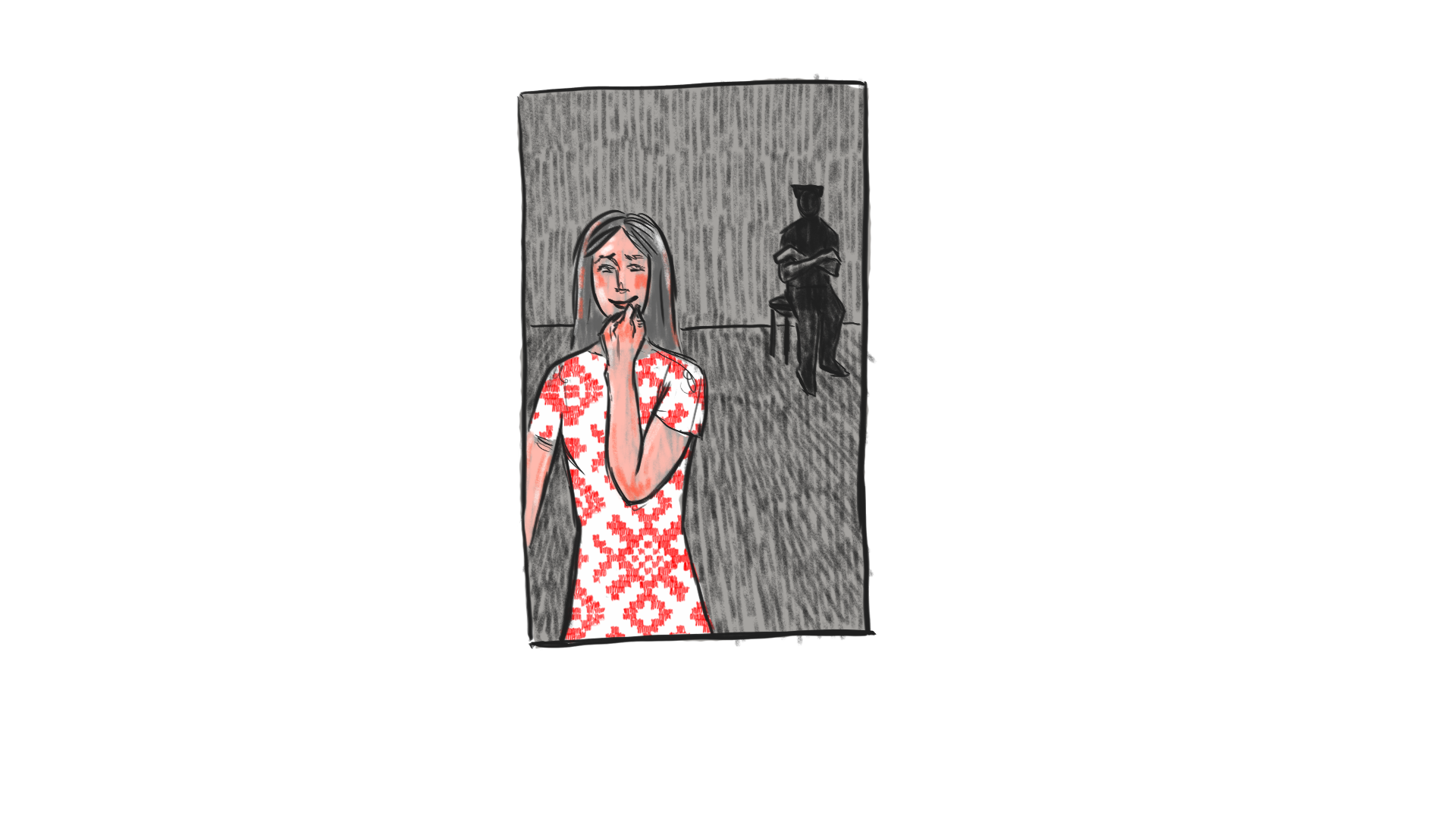

More sweaters, jackets, belts ... More glasses, how many other nearsighted people are out there now, being led like Hanna L? Among the tangled things Nastya B. sees a barbecue set, a grate for grilling. And a DJ console. What state of madness was a person in when he took a barbecue set and a DJ console with him to a protest rally?

Sweaters, jackets, belts, glasses ... A teddy bear. Dang! They arrested a teddy bear or at least someone who walked on the street with a teddy bear. What kind of a terrorist overthrows the government with a teddy bear? They probably demanded a signed statement from him too – “I will never walk on the streets carrying a teddy bear.”

People’s things are piled everywhere in the rooms. Several rows of care packages line up the corridor walls, bags with food that relatives and volunteers lovingly put together for the inmates and that never made it to any cell. What to do with them? Take some? These were supposed to be for us, think the women. But not for me personally, thinks each one to herself. And so, all these bags, smoked sausages, canned food, napkins, toothpaste, books are left on the floor in the prison basement catacombs.

Freedom

Surprisingly none of the inmates of cell #18 remembers the actual release. Was there a door? A lattice fence with a clattering lock? A turnstile? A gateway of some sort where the door behind the released person is locked and she has to wait for the front one to open? No one remembers this moment, this last step towards freedom, like no one remembers their own birth.

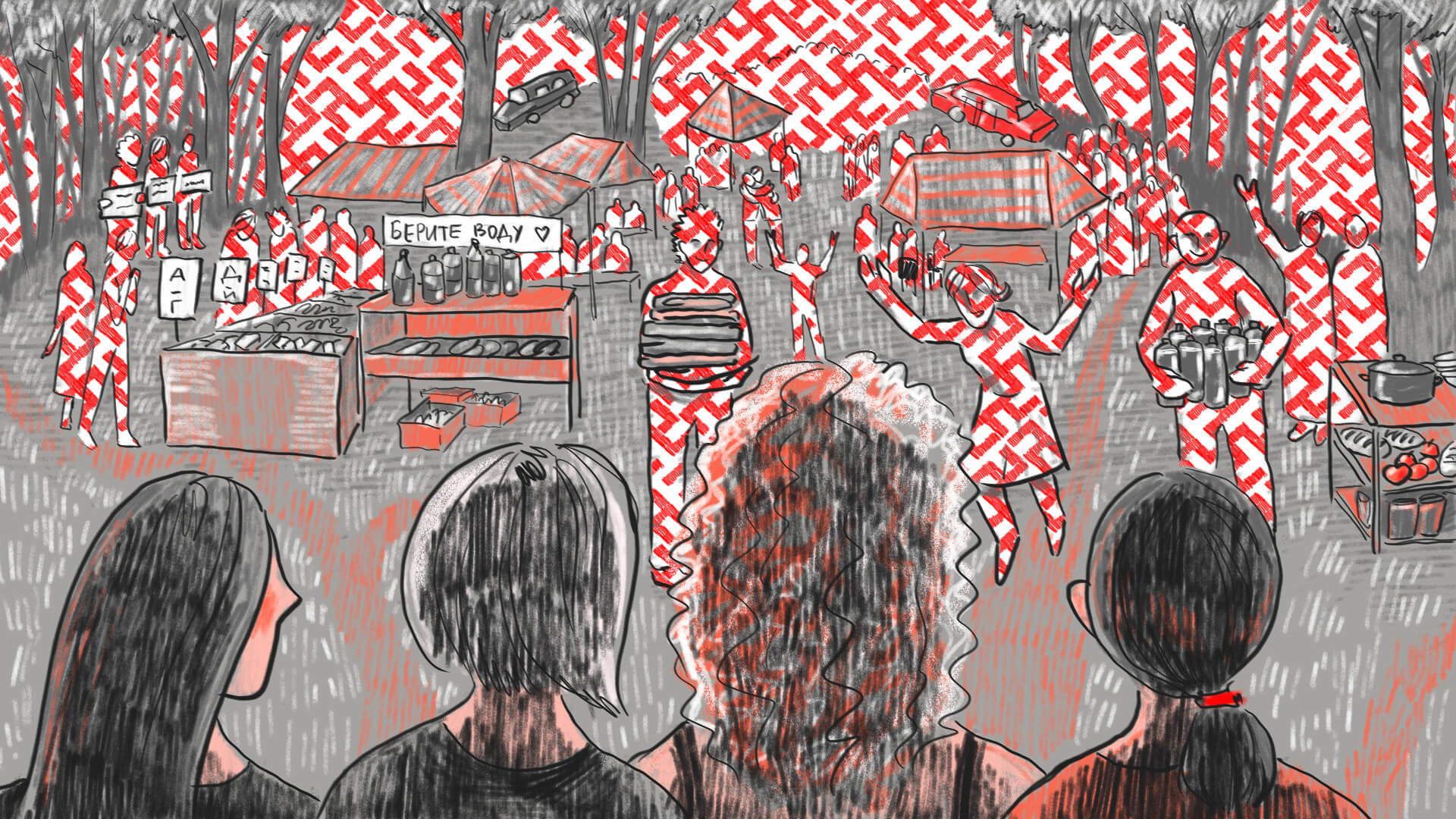

One step - and the suffocating prison noise gives way to a free, happy human hubbub. The street is full of people. The inmates of cell #18 are released closer to nighttime, but people are still there. No one went home, many have flashlights in their hands, and the area looks like a big campground under their light.

Umbrellas, tents, stacks of water bottles and a sign: "Take some." Boxes and a sign: "Ssoboyki for the released." "Ssoboyki" is something you take with you (s soboy) - food, clothing, a small gift - care packages for the road.

But it turns out to be impossible to actually take things yourself. Water and packages simply appear in your hands, several people stuff each released prisoner with all sorts of things at the same time. And all invite to go somewhere.

You can go to consult a lawyer right now, informs a note taped on the tree. You can talk to a psychologist, so what if it’s nighttime? You can go to a prayer, a note with an arrow will show the direction. Bathroom to the right. Lost things to the left. Lists of people still detained showing supposed dates of their release take up an entire stand the size of a billboard. A bit farther away a crowd of people, each with a sheet of paper that says "Driver." Volunteer drivers try to be considerate, never impose. Well, almost never: “miss, let me take you home.”

Almost immediately, despite this hustle and bustle, Lena A. finds her parents. Nastya B. - her husband and father-in-law. Yulia G. - her sister. No one is in a hurry to leave the prison gates as soon as they can. They stand, eat something, talk to a psychologist, check the lists, discuss best routes to see the protesting women in white with flowers on the way home. This state the released and the volunteers are in is close to euphoria.

Only Olesya S. does not find anyone. She is released later than others. They keep her, a Russian citizen, longer in prison to find and return her belongings and thus avoid a possible diplomatic conflict. But neither her things are found, nor the conflict ensues, and she is simply let go after the crowds at the prison gate recede a little.

- I was also released, Olesya says timidly trying to get attention.

The volunteers have their backs on her and cannot hear her, they are busy.

- I'm released too!

One head turns in the crowd, then another, someone is already running towards her.

- Look! Another one of ours! I sense it!

Olesya realizes that volunteers recognized her by her smell. They recognized as one of their own thanks to the unique stench that a person acquires after spending at least a couple of days in jail. Your unique aroma – Okrestina street #18.

And Olesya smiles.