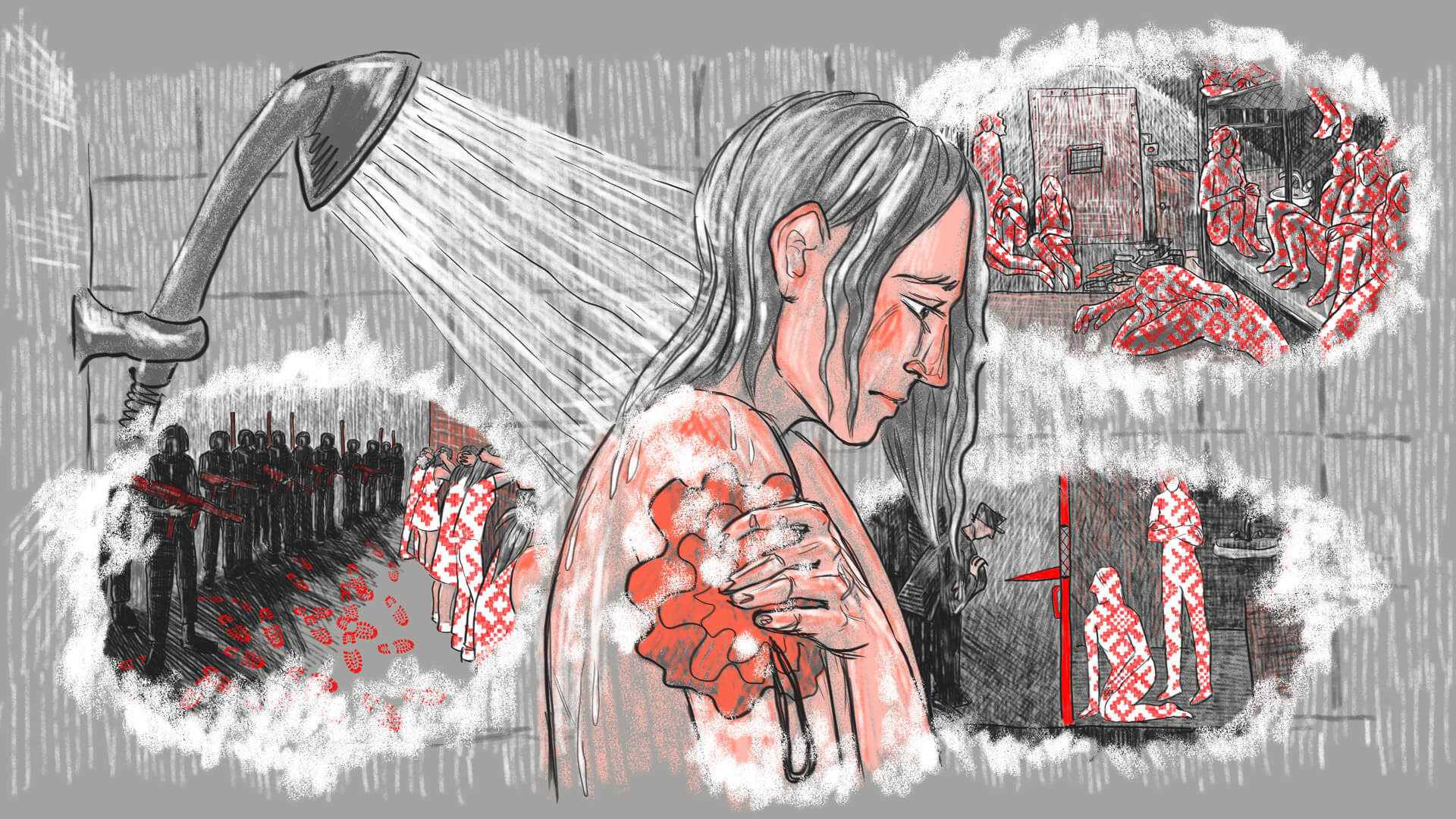

After her release, Nastya B., her husband, and father-in-law do not return to her Minsk apartment, but go straight to Soligorsk, the city of her childhood, to her mother’s. She stands in the shower for several hours and tries to wash off the prison dirt. She scrubs herself with a sponge, but the prison stench would not come off, as if it is deep under her skin.

The skin itself shows plenty of prison traces too. While Nastya is dressing in her room, her mother comes in to give her something and is terrified. Her daughter is covered in bruises. Nastya, her daughter, a young, skinny, with slight limping, chronic spine issues, and a disability. What kind of animals work there? Whose idea was it to beat this girl?

Upset, Nastya's mother goes to the kitchen and makes her daughter a huge bowl of her favorite tomato salad. Homemade tomatoes, it turns out, lift one’s spirit better than a three-hour shower. The next day Nastya drives to Minsk, goes to the doctor and the police to document her injuries, to officially put it on record that she received them in prison.

Almost all the inmates of cell #18 are busy with documenting their injuries in the first couple of days after the release. Because all have at least a couple of bruises, and Olga Pavlova and Olesya S. were severely beaten.

In fact, these first few days cannot be called freedom yet, the prison still keeps them. Injuries are documented and complaints are filed on the same adrenaline rush women survived on when they dealt with the stuffiness, hunger, sleep deprivation and pain in the cell. The same adrenaline that caused Yulia G.’s panic attack. A couple of days pass, the level of the adrenaline in the blood subsides and Nastya B. realizes that she cannot be in Minsk. She wants to hide. Better go back to her mother’s again, but even there it is impossible to hide from the feeling of emptiness, some kind of spiritual brokenness.

Delayed aftermath

After her release, Olesya S. remains in Minsk for a couple of weeks. She hides in her friends’ apartment, but documents her injuries, writes complaints, consults with lawyers, gives interviews so that she does not vanish, is not seized by the Special Services and secretly deported to some place in the bordering Smolensk region in Russia and left on the side of the road like nothing ever happened. She does not want to do any of it, she wants to go home, but she promised her cellmates not to keep silent. Only once this promise is fulfilled does she return home to St. Petersburg and falls ill. She falls ill only there when she finally feels some relief. Olesya’s body temperature stays at 94F degrees for a couple of weeks and she is so week that she cannot lift her head off the pillow.

Olga Pavlova’s stress shows differently. After documenting her injuries and filing all complaints possible, she suddenly realizes that she lost the ability to fear. Literally nothing scares her, filing official complains, marching in all the protest rallies, she is not afraid of anything at all. Not afraid of the heights, speed, cars flying by on the streets, nothing. It is as if Olga lost her self-preservation instinct. And it turns out that people cannot live without it because even in everyday life they do dangerous things like grab a hot pan with their bare hands or attack a burly neighbor for parking his car and blocking the sidewalk. Olga manages to get the elementary human caution back only a month later, and only after seeing a psychiatrist.

Many former prisoners recuperate in Georgia with the help of an international humanitarian program. Mountains, most delicious food in the world, most cordial hospitality help, but the rehabilitation period ends and it is time to go back to Minsk. There the women are overtaken by post-traumatic stress again.

To cope, Olga Pavlova tries to remember and write down every detail of her prison arrest. Yulia G. writes letters to people still in prison, even if she does not know them. Most letters never reach their destination. Replies are also rare but sometimes prison censorship is breached in some mysterious way, and she receives letters frankly oppositional in tone, the ones that end in “Long Live Belarus” instead of “goodbye.”

Zhanna L. and Polina Z. escape their post-traumatic stress in their home community or its Telegram chat. They become celebrities in their neighborhood. A video of their arrest surfaces on the Internet and the neighbors say “see, how can you say this arrest was lawful? Is this regime fair and just when its servants detain and beat people like Zhanna?”

Olesya S. sees her cell in her dreams. Many women dream of it every night. Olesya does not feel fear or confusion, but rage when she dreams. She wants to find her jailers and yell at them “You turned these prison dreams on! Turn them off!” But there is no law or mechanism that can turn such post-traumatic dreams off.

A couple of weeks after the release Katya K. realizes that she is technically still on her honeymoon. And every night during her honeymoon she sees the prison, grenade explosions, and street gunfire in her dreams.

Tanya P. goes to the tattoo parlor. She's one of those people who gets a tattoo in any exciting or turbulent time. Her tattoo artist shows her a random video that shows Tanya being arrested “is that you in the video?” And there it is, evidence to go to court with and challenge her unlawful arrest.

The courts, by the way, willingly reexamine the verdicts that kept the inmates of cell #18 in prison for 5 days. The verdicts are questioned and returned to lower courts for review. And then silence. The judges do not fully cancel their unlawful verdicts from August 10, 2020, but do not affirm them either; do not insist on their correctness, but do not apologize. They simply bide their time, do not make a decision until the official window for reconsideration closes.

The law enforcement system closed in; it is silent. Protests and arrests continue on the streets. Protests weaken, arrests strengthen. Neighbors, friends and new acquaintances rally and support each other. Prison still comes in their dreams. Sooner or later, every inmate of cell #18 thinks “it’s time to leave.”

Emigration

Leaving Belarus is different from leaving Russia. It is more like leaving the Soviet Union – for good. Russian opposition-minded citizens leave, but continue to visit, do not lose touch with their friends, keep their jobs, rent out their apartments in Moscow which helps them to survive in immigration. The Belarusian emigrants are completely certain that return to their homeland almost always means arrest. “She must have felt guilty, otherwise she would not have left in the first place” the officials would think. Although they are not as famous as Navalny, the women feel just like him: you can come home, but straight to prison, though no German Chancellor would try to defend you, no magazine would publish your photo on its cover.

And where is one to go? What is there to do in a foreign land? Lithuania issues humanitarian visas to the Belarusian citizens repressed at home. Hanna L. takes advantage of this, but her career is over. Lithuania does not need musicians who play Belarusian cymbals, Lithuanian musical schools do not teach the instrument.

Poland also issues visas, but at a slow pace. Nastya B. did not have time to wait, her friends kept getting arrested, and she had to leave on a fake work visa. She is lucky to have work that is not connected to politics that she is able to keep, she is an illustrator for a publishing company that prints Christian books.

Ukraine generally accepts everyone. Yulia Filippova moves there and even manages to keep her job in Minsk. But she lives in a hostel, shares a room with another immigrant from Minsk. The situation is livable, but it is not home.

Tanya P. also wanted to leave. Even applied to one of the humanitarian scholarships. But Tanya’s dog got sick right before she was supposed to leave, and she stayed. She could not abandon the dying dog.

In general, it seems that leaving is relatively easy for a single person. Leaving is hard for a person burdened with family. Of course, we hope that staunch fighters like Olga Pavlova stay in Minsk to continue to fight for the rights of the Belarusian people. But there is one more reason – children. It’s one thing to live in a foreign hostel by yourself. It’s a whole other thing to live there with a child too.

Lena A. laughs when she leaves, nostalgia would catch up with her later. Hanna L. does not cry either, but her cymbals that break as she goes through the border control are a metaphor of her cracked life. Not one of the former inmates of cell #18 sees immigration as new possibilities opening in front of them. Everyone wants to come back.

Sometimes these forced Belarusian migrants arrange rallies on the territory of Lithuania or Poland but close to the Belarusian border, to look at their homeland from afar, to block traffic in protest, to stand with posters. Those pine trees over there on the horizon – that’s already Belarus.

Nastya B. and Lena A. meet at one of these rallies on accident.

They cry and hug each other, like sisters.