Hanna L. has always been the “good girl” and an excellent student. Her Russian was wonderful, about as wonderful as her Belarusian. Everyone she knew, from her family to her friends, called her Anya - even though her legal name is Hanna. Out of her official documents, she had two honors diplomas, one from a music school and one from a lyceum run by a conservatory specializing in the cimbalom (Belarusian version of a percussion-stringed musical instrument). After graduating from college, Anya worked at a music school teaching kids how to play the cimbalom and played one herself in the Philharmonic Orchestra. Nowhere in the world does that happen, except in Belarus. Nowhere else can you enjoy huge cimbalom concerts, nowhere else can you find a cimbalomist-virtuoso performing alongside an orchestra of fellow cimbalomists. Anya saw her music as part of the rebirth, advancement, and growth of her national culture. In a neat folder, Anya kept her diploma from the Presidential Fund for talented youth. Alexander Lukashenko’s personal signature shone on that diploma.

Did Hanna want president Lukashenko to be replaced by some other president? Yes, she did, she even took part in concerts in honor of vyshyvanka shirt (traditional embroidered shirt) day, at a point when national symbols had become indistinguishable from opposition symbols. Ever since she was a child, Anya was used to people presuming her good intentions. People always assumed that Anya wanted to do good because she really did – what else could a musician, a teacher, a young lady with thick glasses want?

After the election in August 2020, Anya's intentions were nothing but pure. She was going to participate in the protests as a nurse to provide assistance to protesters who were injured during confrontations with the police. Even if in spite of their armor, their shields and their helmets one of the riot police got hurt, Anya would have helped him too.

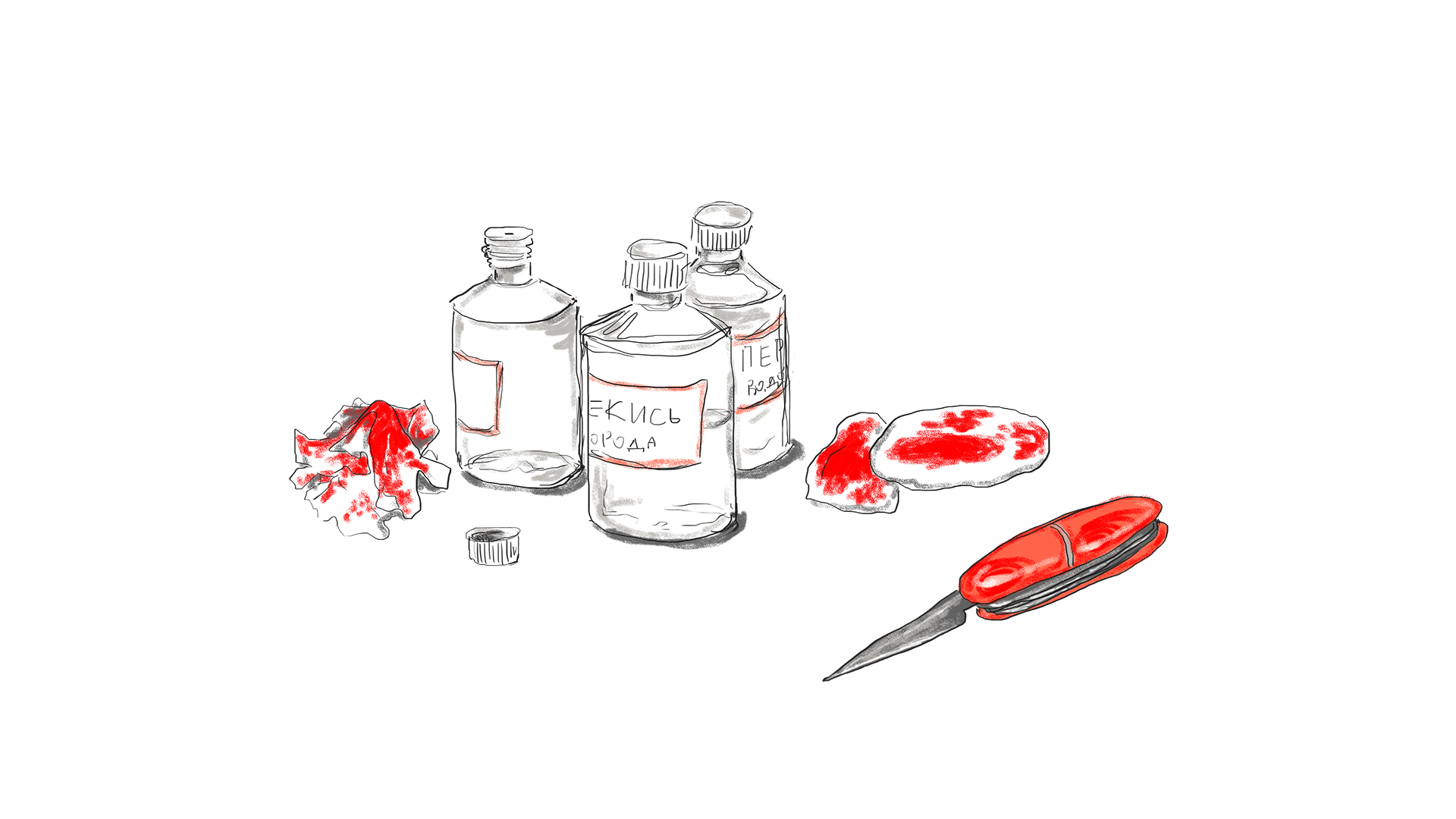

When Anya was detained in the middle of a street for no reason on her way to a rally, she had several bottles of water in her backpack, several bottles of hydrogen peroxide, and some pills. For the first time in Anya's life these simple items were interpreted by the OMON (riot police) officer as dangerous weapons, and despite her short-sightedness and slender frame, Hanna was labeled a terrorist. What's in the bottles? Something flammable, a Molotov cocktail? Why do you have those flasks? To bomb the police with them? What about the pills? Drugs to pump up insurgents storming government buildings? "Oh my God, what are they on about!" – Anya thought to herself.

Things got easier at the police station. The head of the station called Anya "girlie" and told her that she looked like his daughter. He placed all the detainees in a gym and allowed Anya to help the wounded. Anya had a small pocket knife. She used it to cut the plastic zip ties tying men’s hands behind their backs. They were so tight that while the detainees were being transported to the police station, their hands turned blue and bloody scars were cut into their wrists.

Despite being detained illegally, Anya felt she was where she needed to be in the police station. She managed to help many people. But she could not even imagine that her actions would once again be interpreted as terrorism. Unknown people in black riot gear broke into the gym and started beating the men. One of them noticed the medicine laying next to Anya on the floor.

- Who’s the smartass that brought the medicine? Which one of you bitches?

Anya was scared to say that the medicine was hers. But staying silent would have meant the riot policemen beating many men in their search for the "wannabe doctor". Anya confessed. She and her friend weren’t beaten, just screamed at:

- So you bitches wanted to play nurse huh?

Anya suffered another injustice because of her pocket knife. When Anya was taken to be interrogated by the investigator, the knife was in her pocket. Before the interrogation, she was searched:

- Wanted to stab me with that knife, didn’t you? – the investigator said as she entered into the police report that during the arrest, a knife was confiscated from citizen L.

- What knife? This is barely a pocket knife! – Anya almost started crying.

She did start crying at the trial, when the judge, nicknamed Mister Prison Days, sentenced her to six days in jail. For what? How? What will I tell the kids at school? “Children, we won't have lessons this week because the teacher is in jail!”

She hasn’t cried since. She simply kept adding up all the cruelty she experienced and compared it to movies about the Great Patriotic War and the atrocities of the Nazis. Her glasses were taken away, so Anya was virtually blind. There were 36 women in a four-bed cell with no air to breathe and no place to sit. Anya was sitting on the nightstand, and Nastya B. was sitting inside of it. Hanna was taken out into the prison yard where military men were holding machine guns. They put her face against the wall. Anya thought: "They’re going to gun me down." That thought rang in her mind until the second, then the third, and finally the fourth line of detainees was pressed up against her back. "No, they won't shoot."

She was taken from the Center for the Isolation of Offenders (CIP) on Okrestina Street to the prison in the town of Zhodino. There she was taken into an empty tiled room with pipes sticking out of the ceiling. “This is a gas chamber”, Anya thought. “They’re going to gas us.” But no, the room turned out to be a shower room. The detainees weren’t brought there to wash off, but were kept there temporarily before being distributed to their cells. They never gave her a chance to shower. She was only fed on her third day in Zhodino.

After her release, Anya spent several hours in her bathtub scrubbing herself with a loofah almost to the point of bleeding, trying desperately to wash off everything that happened. But it couldn’t be washed off. She tried to sleep, to escape into unconsciousness, but she couldn’t.

From August to December, Anya couldn’t sleep for more than a few minutes, after which she would inevitably shudder awake and jump up in a cold sweat.

Anya began to perform yard concerts. She went out to her house’s yard, to the next one over, and to ones further and further away – she played the guitar and sang. Protest songs? After the inhuman cruelty she experienced, any human song is a song of protest. In a country of stolen votes and voices, any human voice is a vote “against”.

After several backyard concerts, strange men began to call Anya. They introduced themselves as district police officers, investigators, captains, majors and made it clear that all of Anya's concerts were being watched, and that the reports were being put in her personal folder, adding up to an administrative or even criminal case. Her lawyer confirmed it: singing with a guitar in her own yard was now enough to be arrested.

So Anya left for Lithuania. In Vilnius, for the first time in four months, she calmly fell asleep and slept through the entire night. Meanwhile, Anya was fired from her job at home in Minsk. She is no longer a philharmonic musician or a music school teacher. She now makes ends meet by writing small blurbs for different publications.

Anya hadn’t been working long enough at the philharmonic society and the school for the government to consider her taxes as sufficient compensation for her free education. Now Anya must pay back in full the cost of her education to the Belarusian state. The same state that grabbed her off the street, kept her in prison for almost a week, barely fed her, and insulted her.

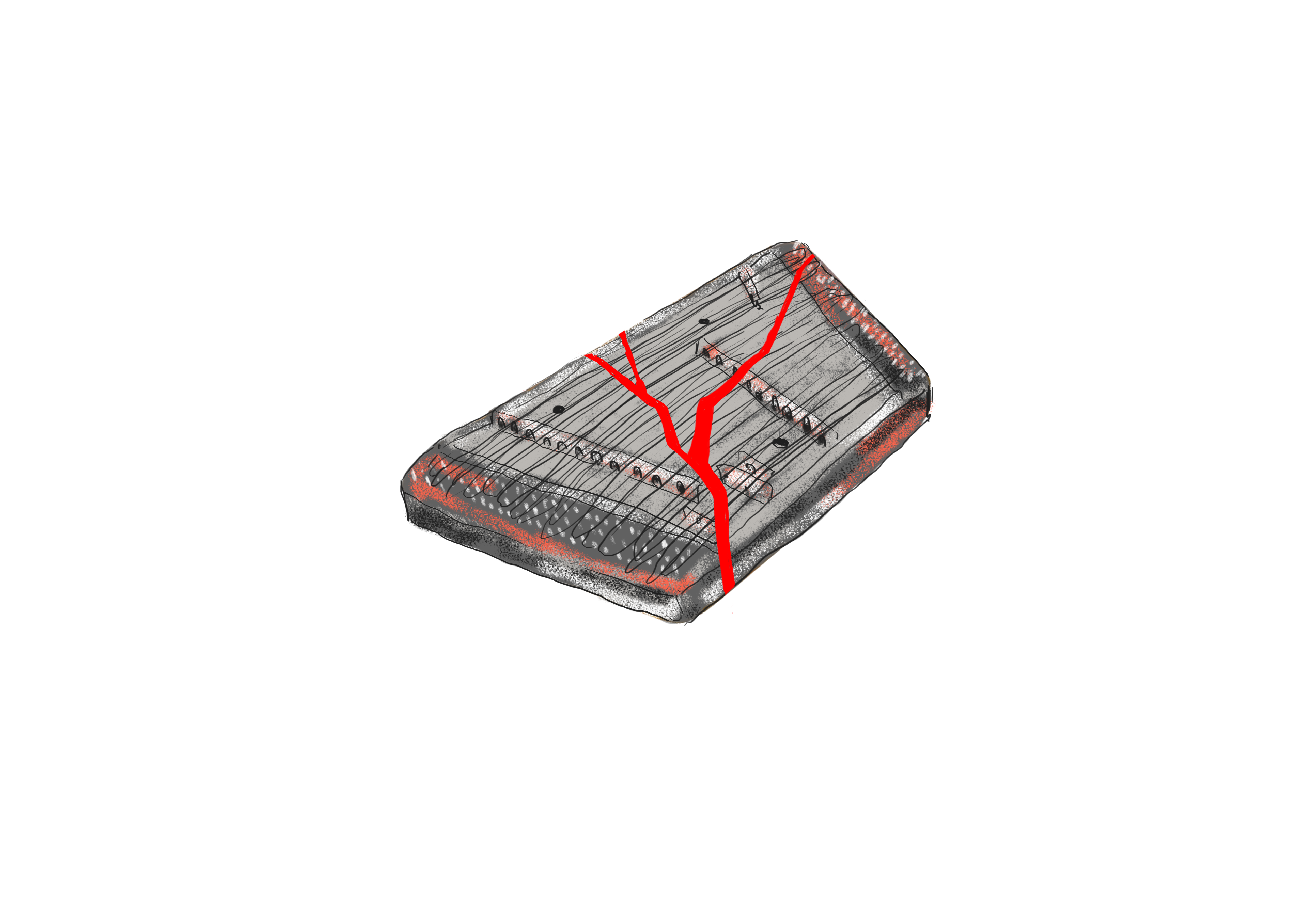

Anya’s father sent her cimbalom to Vilnius. Either in shipping or at customs, the instrument dried out and the soundboard cracked, now the instrument needs repair. Not in Lithuania, nor anywhere else in the world does that happen, except in Belarus. Nowhere else can you enjoy huge cimbalom concerts, nowhere else can you find a cimbalomist-virtuoso performing alongside an orchestra of fellow cimbalomists. In Western Europe, cymbalomists sometimes perform on the streets, begging for spare change from passers-by.