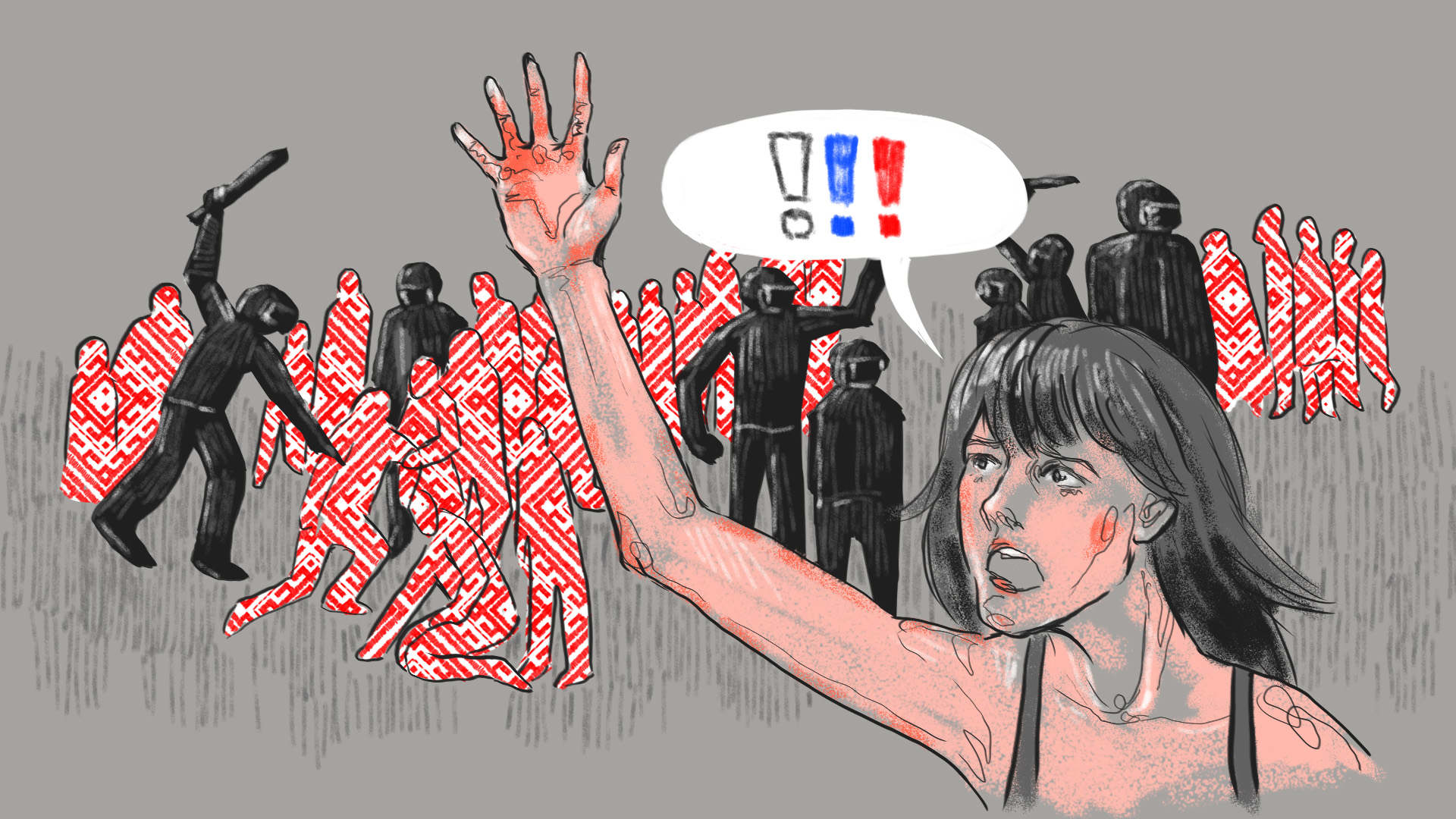

Olesya S. imagined that only cruel people serve in the Belarusian riot police. Even some with sadistic tendencies, some just decisive and tough, but still people. Whenever Olesya ran into a chain of riot police in St. Petersburg, whether during the World Cup or during protests, it was possible to talk to the people in the chain. They smiled in response to Olesya's smile, they enjoyed talking to a beautiful young woman, and they answered Olesya’s questions if the questions were specific and allowed a simple answer:

-Can I come through?

- You can, just keep to the right.

- Can I come through over here?

- Not here, use the next street over.

Once in St. Petersburg, when protesters began to be detained during an unauthorized rally, a young riot policeman even said to Olesya:

- Madam, it's messy here now, go behind our chain, it's safer here.

Olesya came in and waited behind the backs of the strong SWAT guys, while other strong riot policemen were twisting the hands of male protesters, who were also quite strong. It was like that in St. Petersburg, and Olesya thought it was like that everywhere.

But this is not the case in Minsk.

Olesya arrived in Minsk with her boyfriend, a Belarusian guy working for a St. Petersburg company. It was a business trip, well, an opportunity to get away from it all and participate in the election.

They walked down the street in the evening and ran into a chain of riot police, Olesya asked:

- Can we pass?

- No.

- Why? - Olesya asked again because people were strolling around on the other side of the chain.

- Alright, go ahead then.

The young couple took a step through the chain and their arms were immediately twisted behind their backs and they were both taken to the prisoner transport vehicle. In the police van they started beating Olesya’s boyfriend.

- What's going on? Who are you? - shouted Olesya.

And here it is! The riot policemen answered Olesya:

- We are nobody.

Not only did they not give their names, ranks, or positions, they acted as if it was not them, not here, that they weren’t detaining Olesya and weren’t beating Olesya's boyfriend.

- What's happening? - shouted Olesya. - Are we under arrest? Detained?

- No, - answered the nobodies in riot gear. - Not detained.

- So can I leave? - Olesya started walking towards the exit.

- Try.

At the door, Olesya’s hands were tied behind her back and she was put back into the bowels of the vehicle.

From that moment on, Olesya observed not only the dehumanization of law enforcement officers around her, but also her own dehumanization. In the prison corridors, seeing how the men were being beaten, Olesya shouted:

- Why are you beating them?

- Am I beating them? - answered the guard and continued the beating.

They ripped off Olesya's rings, tearing the skin off her fingers until they bled. She was slapped hard across the face a couple oftimes. She was shoved so hard that her face hit the wall. As if she, Olesya S, was no longer there. As if she would never leave, would not complain, would not go to the doctor to record her injuries.

She said that she was a citizen of Russia and demanded to speak with the consul. But the jailers only laughed at her and said: "I don't give a damn about your Russia!” as if they didn’t know about the existence of a powerful country right next to Belarus that is obligated to protect its citizens.

However, as it turned out later, Olesya’s friends who evaded arrest tried to call the Russian embassy, but the consul didn’t even consider going to the prison to release a Russian citizen, as if Russia really did not exist.

Olesya understood her non-existence with horror. A police report was not drawn up against Olesya. Olesya was not put on trial. But at the same time, she was kept in prison. And she shouted:

- You forgot about me! Give me a police report! Put me on trial!

When some cellmates were beginning to be released, Olesya pleaded:

- Remember me, I am Olesya S. from Russia, from St. Petersburg. Remember me, tell them that I am here.

She seriously feared that not knowing how to register the arrest and detention of her, a foreign citizen, the Belarusian jailers would simply kill her and dispose of her body.

And with no less fear, Olesya discovered that her reaction to her own dehumanization was to protest. She was afraid to resist, but she could not help herself - she resisted.

When they brought her to the Center for Isolation of Offenders (TIC) on Okrestina Street and commanded: “Run, bitches, run!” Olesya suddenly shouted:

- You do the running bitches!

The next second, fear gripped her: they’ll kill me. But no, they didn't.

In a cell where 36 people were huddled together in a space of eleven square meters, Olesya suddenly found it necessary to wash her hair. And she washed it - under the only faucet above the sink, with a drop of tar shampoo left by one of the former prisoners.

When the time came for the prisoners of cell #18 to be released, they were taken one by one to some important boss to repent and sign a piece of paper promising never to participate in any protests again. The women were led into an office and placed in front of a large mirror. The police commander sat to the side and slightly behind them, they weren’t allowed to look at him. They were supposed to repent while looking at themselves in the mirror.

But Olesya began to spin and flirt in front of the mirror:

- Oh! I’ve lost so much weight. And look at how radiant my skin is!

When they were all being released, Olesya saw some important general in the prison yard that could have even been the Minister of Internal Affairs, and shouted at him:

- I am a Russian citizen! Give me my belongings back! - although any normal prisoner would be happy to leave the prison, with their belongings or not.

The general ordered that Olesya's stuff be returned, and under the pretext of searching for her things they left her behind bars for a couple of extra hours, while all her former cellmates had already been released.

Olesya was released alone. The volunteers waiting at the prison gates with food, phones, and shoelaces were busy with other newly released prisoners. No one realized that Olesya, too, had just been released. Olesya was again scared that she didn’t exist, that she was nobody:

- Wait! I was just released too! Smell me!

It was the foul smell emanating from Olesya that unmistakably identified her as a recent prisoner.

The next day, Olesya returned with her boyfriend to the jail on Okrestina Street to pick up her things. There, at the gates of the prison, Olesya experienced a strange and very strong feeling - she felt like she was being pulled inside. She really wanted to return. To those blood-stained concrete corridors. Return to the cell where people are stuffed together like sardines in a can.

Olesya does not know how that strange feeling works. Perhaps just like a fear of heights. In the mountains or on the upper floors of skyscrapers, people who are afraid of heights are irresistibly drawn to jump down.

For every minute before leaving Minsk, Olesya tried to busy herself, giving interviews to anyone and everyone. As if trying to affirm: I’m here, I exist, I am Olesya S. When Olesya finally returned to St. Petersburg, her body shut down. For several weeks she was bedridden, running a fever of 34.2C, and could not get up. And for several months, her dreams were almost all filled with cell #18.