- Niiiiine AAAAAAM! The sound comes through the crack in the cell window that Olga Pavlova managed to make.

- Niiiiine AAAAAAM in the moooorniiiiing!

The light in the cell is always on, it is hard to understand what time it is. The usual prison schedule - wake up, breakfast, roll call, lunch, walk, dinner, bedtime - there isn’t any of it, the guards are too busy. The sense of time is completely gone and if it were not for the volunteers who camp out by the prison gates and yell out time now and then, the inmates of cell #18 would have no idea whether they spent three hours here, three days, three hundred days or if the world ended out there, on the outside, and the women were simply forgotten in the cell, not taken into eternity.

- Tweeelve Peeeeemmm!

This means that life continues, time goes by, the jail sentence decreases. It also means that there is a whole crowd out there, by the prison gates, in solidarity with you.

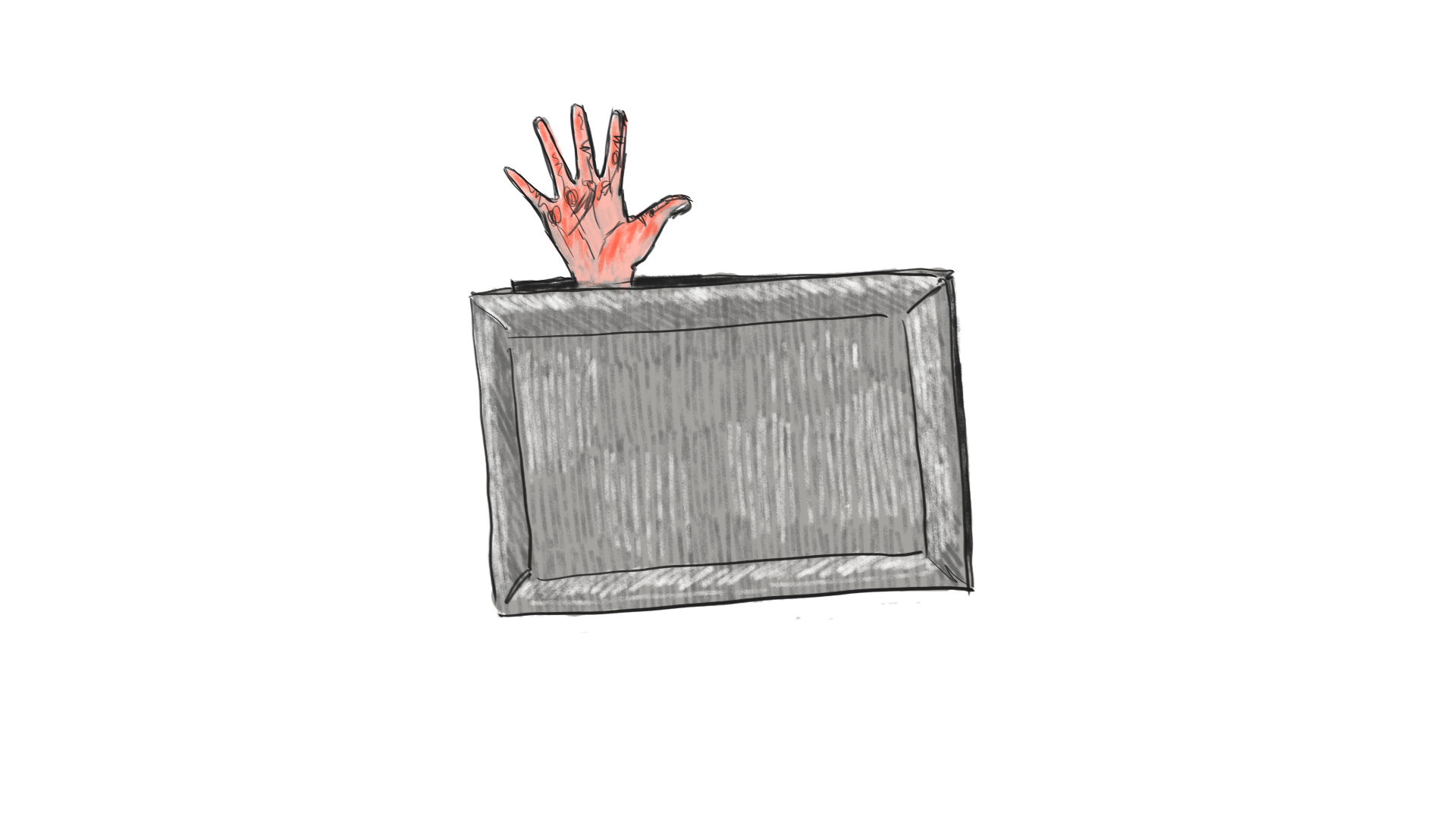

Olga Pavlova can’t see the volunteers behind the prison wall, but she squeezes in her hand through the crack between the window frame and the bars and signals to someone out there fanning her fingers: five, five days, she was sentenced to five days of arrest.

The volunteers see a woman's hand in the prison window over the wall and even guess that it is signaling something, but what? There are five of us here? The fingers clench and unclench. What does this mean? Add these fives? So, five, ten, fifteen, twenty? They were given twenty days? Twenty years? There are twenty of them there? “Can’t be this many in one, all Okrestina cells are small,” say the volunteers who had been jailed there before, the ones that gave a tip about yelling the time.

The volunteers also cry out names, though not quite clear whose. Their own? Like, “so-and-so is standing here,” or “heed me, my beloved so-and-so?” Or, on the contrary, maybe they shout prisoners’ names, those who are missing, who can’t be found, and so they yell hoping that the inmates would show some kind of a signal or at least know that they are being looked for? Olga Pavlova is inclined to think the latter and decides that if she hears a cellmate’s name among the ones the volunteers are yelling, she will show a thumbs up. But they mostly yell out men’s names.

The most important thing is to shout at least something. Any sound from the outside tells the prisoners that someone is thinking of them.

Burglars and climbers

While sitting in jail, demanding a meeting with the Russian consul, and getting no help from the Motherland, Olesya S. is hoping that one of her friends is currently calling the Russian Embassy. After her release she finds out that yes, they all called, flooded it with phone calls.

Zhanna L. and Polina Z. are worried about their dog. “How is my doggie there,” thinks Zhanna since her husband was also arrested right in front of her. When Zhanna is released, she finds out that the dog is OK. The husband was beaten, but released, the dog was found. To save the dogs in the apartments where whole families were arrested real rescue operations were conducted. Volunteers organized a brigade of professional mountain climbers. On a tip from neighbors, they climbed through the windows, fed, and walked the animals.

There was also a team of burglars organized. If everyone who lived in the apartment was arrested and a dog was left behind the locked door for five days, they neatly broke in, walked the dog, fed it, changed the lock and upon their release the owners got a happy dog and new keys to the apartment. How is this possible, you ask? How is it possible to have a team of Robin Hoods in a city? Because everyone understands the absurdity of all these arrests and the necessity of breaking in, that’s how. The neighbors understand, the housing association does too, even the beat policeman is no stranger to solidarity.

Children, by the way, if left without supervision due to parents’ arrest, are taken in by neighbors and relatives.

When Katya K. sits in the cell, she is mostly tormented by two thoughts: how to find her husband who was arrested with her and whether she will get fired for this unforeseen absence. After her release she learns that not only was she not fired, but she was actually given a bonus to do post prison rehabilitation. And someone smuggled a cellphone into her husband’s cell, so he managed to call and tell where he was and his release date. Yulia Filippova is also worried about being fired and agonizes about her elderly mother without her. After her release she finds out that while Yulia was in prison, her boss called her mother, offered to bring her food and money, and then gave Yulia a vacation to recuperate after prison.

In Zhodino, where many prisoners were transported to by the end of the third day, people opened doors, apartments and entrances to volunteers and prisoners' relatives who kept watch by the prison walls and offered them to spend the night, eat, wash, go to the bathroom. And nothing went missing. Not one thief took advantage of the wide-open doors, no unlocked apartment was robbed.

One thing has to be mentioned about thieves, by the way. When the inmates of cell #18 were brought to Zhodino, seasoned burglars staged a riot there and screamed that they might deserve to be jailed here, but the girls didn’t. They demanded that the authorities let them go immediately.

Laces and prayers

When female inmates of cell #18 were transferred from Okrestina street to Zhodino, the van they were in drove through the crowd of volunteers. The older ones baptized the arrested, wept after them and prayed. The liturgy of the detained: “Though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.” The younger ones peered through the windows. Not out of idle curiosity, no, but in hopes of recognizing at least someone. This is what happened to Tanya P. Her father’s friend recognized her, found him, and told him that his daughter was alive, seemed OK and was transferred to jail in Zhodino.

And when the prisoners were released, volunteers had heaps of presents for them. Yulia G., Olesya S., Hanna L. remember a pile of laces. The guards took their own laces during the intake and never returned them, but here the women could pick new ones, of any color or length. Clothes, too, for men, women, children, all sorts of things. The ones you are wearing are torn, dirty, saturated with prison stench so here you are, choose whatever you want and put it on. No charge.

Yulia Filippova hardly made a step out of prison when a woman ran up to her with a bowl of hot borscht. How did she even manage to heat it up around here? The soup was thick and heavy, a spoon would stand in it, the woman clearly put all her heart and soul in it. But Yulia did not eat for four days and was afraid that her stomach would not be able to handle it, so she asked if there was anything lighter to eat, maybe an apple. An apple? Oh sweetheart! And just like that, there were 6 pounds of apples for Yulia, of different kind, sweet, sour, shiny ones from the store or homegrown fresh off the tree.

During their release from Zhodino, our inmates worried how they would get home without any money for a train ticket, the guards didn’t return the money either. But no one had to spend a dime to get home. Whoever was not picked up by the relatives, got a ride from the volunteers. Dozens of them drove to Zhodino wanting to give rides to the released.

A tall man approached Olesya S. and offered to take her home. Olesya got scared for a second. She was freed closer to nightfall, feared being in a car alone, with an unknown man, driving through the forests. But it turned out the volunteer took care of this too and had his daughter with him. The girl sat with them in the car, a sign of good intentions and trust.

Frequently, even if it was out of their way, taxi drivers and volunteers drove the released women through downtown to look around – these were the most beautiful days of the protest, women in white with flowers everywhere, their beauty, tenderness and vulnerability were also a protest.

And there were volunteer lawyers to help document the beating and formulate complaints. Volunteer psychologists so that people could talk about what happened to them, right by the prison walls if they wanted or later. There were entire teams formed to sort through piles of things all mixed up in prison and to locate their owners.

When the inmates got home and went online, they discovered they had been flooded with messages of support on social network. All these five days of imprisonment their friends and strangers were writing them words of sympathy. Lena A. read these messages of solidarity ... nii-ne hoo-urs…