Nastya B. says that on the fourth day in prison, right after they were transferred from Okrestina street to Zhodino, female inmates of cell #18 experienced menstrual synchrony. All simultaneously needed hygienic pads and, thank god, they had them in Zhodino.

This is a well-known biological phenomenon, the McClintock effect. It helps the pride when cubs are born at about the same time. Cubs are most vulnerable. If they are born at different times, the predators will exterminate them one by one. If they are born at the same time, then someone will be saved, and the period of particular danger to the pride will be relatively short. This is the strategy for the conservation of the biological species.

If two students share a dorm room, their cycles are synchronized in a couple of months. It is possible that in prison biological organisms respond quicker than in campus setting.

If two biology students share a room, they wait for the McClintock effect and observe with interest which girl the periods will synchronize after. The one who’s better at studying? The one who’s more popular with the guys? The physically stronger one? Richer? The girl, whose cycle remains the same, while her friends’ change and begin to follow hers, is the alpha female in the pride. And a small female collective is a pride, a flock, a matriarchal family - a community regulated not by common political views, common ideological aspirations, even common interests, but by the ancient biological mechanism of collective survival.

To be fair, scientists repeatedly doubted the existence of the McClintock effect and explained it by statistical errors or even people’s simple desire to believe that such an effect exists. Here is the thing, it does not matter to us whether the McClintock effect exists in real life. What matters is that the inmates of cell #18 believe that during their six days of suffering a biological, stronger than anything, animal bond formed between them.

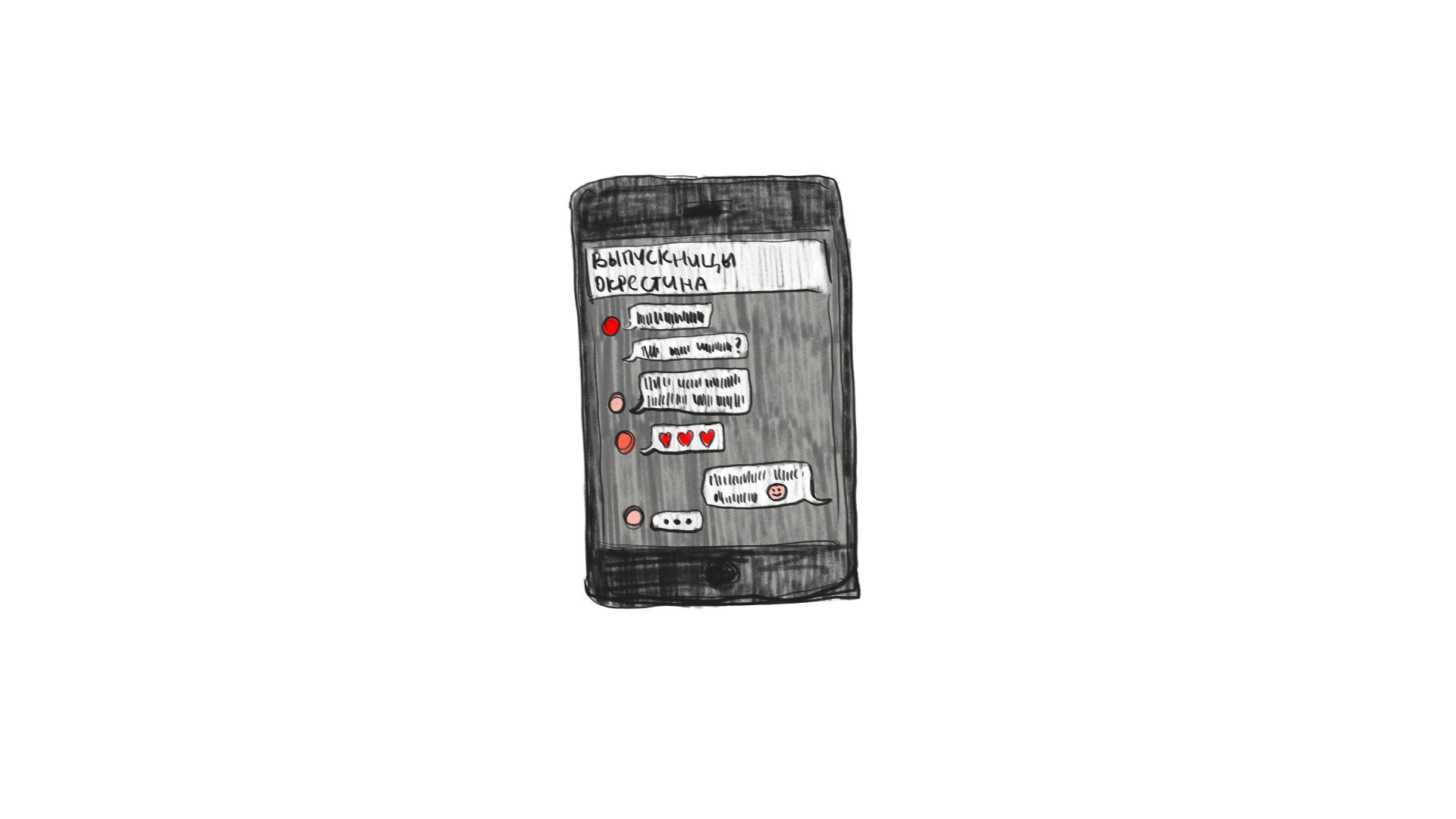

Graduates of Okrestina street

They call themselves Okrestina graduates and have been corresponding with each other for almost a year now which at first makes no practical sense at all. Why write each other, recall prison life details, and ask how everyone is doing now? You do not write to random people you shared a hospital ward with, for example. But they write.

There, in the cell, with no phones, pencils, pens, a single scrap of paper, they were giving each other their phone numbers. But it was hard to keep them all in one’s head, so they chose the easiest one and memorized it. And then, once freed, they all texted that number to reconnect.

There, in the cell, they vowed to each other that, once free, they would not keep silent and would speak out about this stuffiness, hunger, fear, beatings of men. In large part it is because of this vow the project that you are reading now became possible.

After the release, when the hormonal storm of stress subsided a little, many inmates of cell #18, especially those who did not leave Belarus, would have liked to keep quiet. Not feeling safe, they would have preferred to hide, but the vow bound them. They say that they sacrifice their personal interests for the sake of other Okrestina graduates, for the sake of the interests of that pride that developed there, in cell #18.

What’s it for, this pride? What does it mean? Cats in a lion's pride hunt together. Dolphins of a pod all push the newborn cub to water surface for its first breath of air. In ancient human tribes women gathered food together. But this prison pride, what’s its purpose? Why this loyalty to it? What’s its value?

Pride rules

Talking about these six days in prison, this lawlessness, pain, sufferings, and humiliations each inmate of cell #18 always remembers something she is ashamed of.

Already in the police precinct, before prison, Hanna L. met a woman named Aleksandra and did not help her. Later this Alexandra was taken by the policemen to the forest, threatened with rape, beaten, suffered torn leg ligaments, and instead of the compensation the court found her guilty and sentenced her to three years of “home chemistry”, i.e. limitation of rights and close police supervision. And Hanna did not help her. How could she have helped, herself in a police cage? That’s the point, she couldn’t have, and this is what she is now so ashamed of.

Lena A. is ashamed that as an independent observer she was not able to make sure the vote count was honest, even though independent observers were not even given access to monitor it in the first place. She was not able to do the impossible but is ashamed all the same.

Yulia Filipova is ashamed that in the prison cell, not even she personally, but some other girls, admonished Olesya S. for her Russian citizenship. “It’s because of Putin’s support that Lukashenko’s regime is showing such cruelty,” they said. They started these conversations and immediately stopped. But shame remained. And Zhanna L. is ashamed of the same. Everyone is ashamed of something.

So, shame. The first rule of the pride. A decent person always has something to be ashamed of. It is good to become aware of your wrongdoing and express your shame out loud.

All cellmates are ashamed of their remarks about Putin and Russia’s role in the Belarusian terror they made in moments of despair, but Olesya herself does not remember this: “No, no one said anything bad about me being Russian. No, nothing like that.” No one remembers other similar offences. Indirectly, through some slips of the tongue it becomes clear that in extreme crowdedness domestic disputes happened all the time - where to sit, how to stand up, how to get through, where to put your foot down - but no one remembers them. “No, all girls were polite, no one quarreled. There were two women, let’s say, of a lower social status, but even they behaved.”

Hence, the second rule – open-heartedness. No need to hold on to wrongdoings. The inmates of cell #18 do not wish similar suffering for their torturers, all those policemen and prison guards. The only revenge they seek is disciplinary penalties and punishment dispensed after an official investigation of a legally filed complaint.

These are rather pointless complaints, but the women help each other formulate them right in the cell, not writing them down on paper, but memorizing them by heart. Because it is not about complaints but about compassion. "I feel for you, and I am trying to help."

And if you ask how Hanna L. should have helped Alexandra in the precinct, it is exactly like this, by showing compassion. Instead, she withdrew, still in shock from her sudden arrest. Though she should have shown compassion and done something. Should have put some hydrogen peroxide on her, had she any, no matter how nonsensical that would have seemed. So, the third rule of the pride is compassion. Have it and show it in any way you can. Just like Zhanna L. does when she comforts Yulia G., pats her on the head when she suffers a panic attack.

The fourth rule is weakness. It is OK to be weak and there should be no shame whatsoever in showing weakness. I am scared, I am hurting, I cannot stand my dirty body, the lump in the mattress looks like a rat for a second and here I am shrieking like crazy (Olesya S.) and my friends around me are laughing and patting me on my back. Show weakness, otherwise how else would girlfriends be able to show their compassion? And compassion, remember, is the third rule of the pride.

Finally, the fifth rule of the pride is courage. It is scary when men are being beaten. It is even scarier to demand to stop the beatings, but you demand. It is scary to even approach government buildings after the release, but you go in. You go to the prison on Okrestina street to pick up your and your fiancé’s things (Olesya S.). You go to the Investigative Committee to file a complaint (almost all except Yulia G.).

Yulia G. goes to protest marches instead. Every one of them that takes place after her release. And Hanna L. is scared to give concerts during block parties that sprung up all over Minsk neighborhoods as people consolidated in protest, but she plays. And Lena A. is scared to participate in her student organization, but she does. Hannah is threatened and forced to emigrate. Lena has denunciations written on her and has to flee too. Yulia G. is thrown in jail three more times. Is it scary to end up back in prison after you just got out of prison? Yes. But you go, these are the rules of the pride.

A remedy for cruelty

These rules seem absurd, impracticable. Can protests really succeed if the protesters are full of shame, have open hearts, compassion and can paradoxically show weakness and strength at the same time? No, they can't. This is not how revolutions are made. Political regimes don’t get changed like this.

However, the country is run by people (or, should we say, one person?) whose values are exactly the opposite to the basic rules of the pride. These people are ashamed of nothing, do not have open hearts, do not sympathize with anyone, never show weakness and fear everything in the world, even unarmed women on the streets.

The absence of shame, open-heartedness, compassion, weakness, and courage form the main quality of the Belarusian regime – cruelty. Pride rules, therefore, are the alternative.