You’ll say, ‘come on, it was only five days.’ Five days of, sure, absolutely illegal arrest and completely unsanitary prison confinement, but only five days. Is it necessary to take it all so seriously in a country where some elderly people still remember how millions were sent to exile and sentenced to decades of hard labor camps? Did arrests look like this three -quarters of a century ago? Did tortures? Did young women leave Stalinist camps with merely a post-traumatic stress disorder and a couple of bruises? No, they did not leave at all, or left as crushed old women. So, should we not admit that the current regime in Belarus, though no doubt tyrannical, is still a lot more benign than its predecessors?

If we look at simple statistical figures, this would be true: fewer arrests, lighter tortures, faster releases, borders are open, run, if you want.

But the thing is, throughout our investigation we have not found a single case (except for the Tale of a Truly Good Cop) where unlawful arrests and prison confinement were constrained by moral considerations, considerations of pity, compassion, mercy and open-heartedness.

Logistics problems

It was the logistical issues that held back the repressive apparatus. The only reason they grabbed as many people as they did at the polling stations and protest rallies was that they ran out of space in their vans. If Minsk riot police had endless vans, what would have prevented them from arresting the entire city? Definitely not the obvious innocence of the detained. Of the eleven women we talked to maybe six were somehow connected to the protest movement. And not a single one did anything illegal. They were arrested simply because there was some space in the van. And the others were not arrested because there was not any space, there are no other reasons.

The women were released a week earlier than stipulated in the court documents also, it seems, because of logistical reasons. Cells simply got overcrowded. The convoy and the kitchen simply couldn’t catch up. Someone had enough mind to realize that if they did not let these unfortunates out, they would be carrying out the bodies of women who died of dehydration and heat strokes. They just did not want to deal with the corpses, what other explanations can there be?

Throughout this story, we have not heard a single mentioning of a servant of the regime who would say “stop torturing these girls” (only convicted criminals in Zhodino said this), “take mercy on them,” “let’s do this humanely.” No one committed an action based on pity and compassion. Some resorted to cruelty because they were obeying an order, some - because they enjoyed it. But no one rejected it.

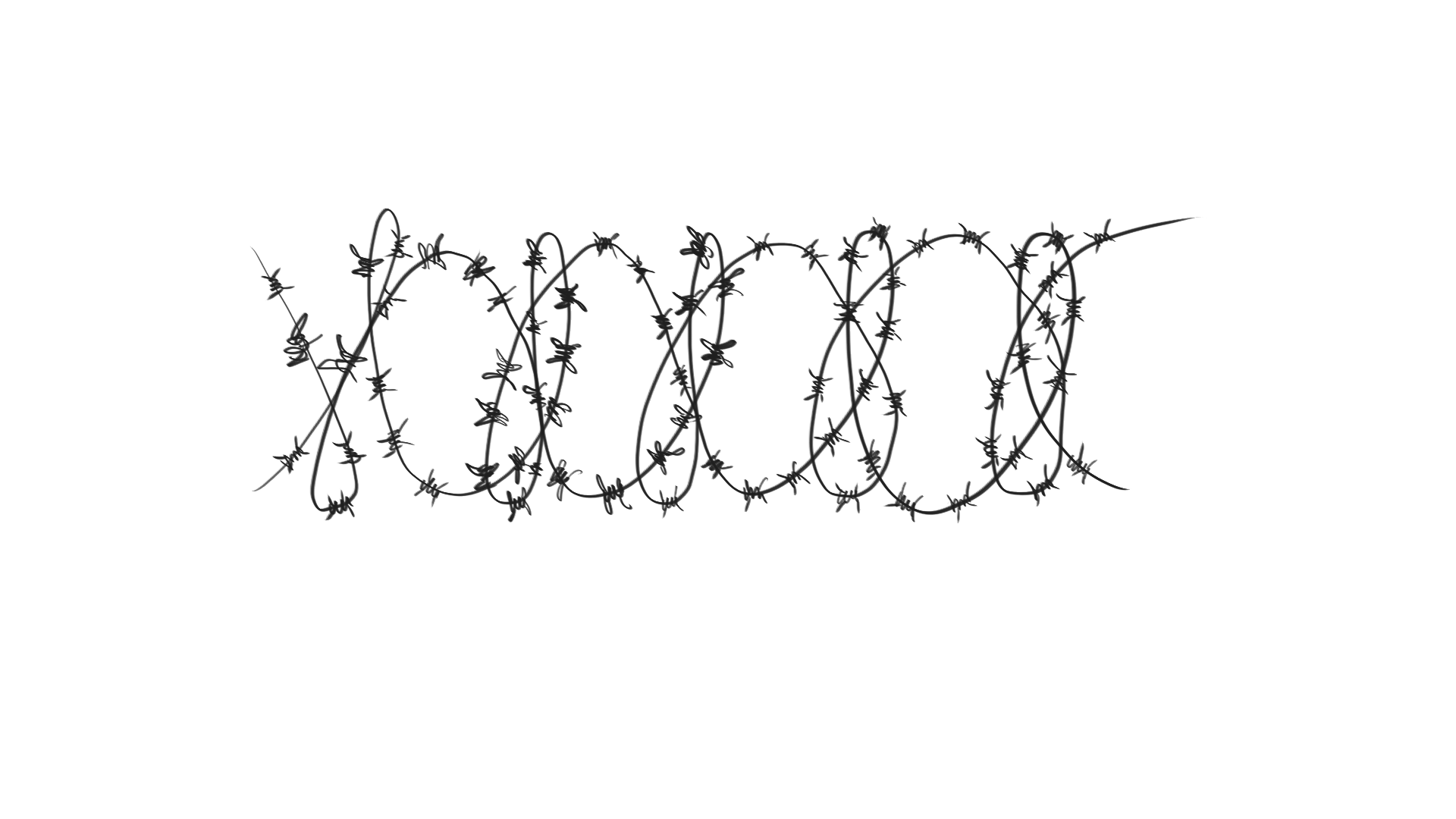

You say that “home chemistry,” confinement in one’s own apartment is way more humane than confinement in prison? But we told you in the last chapter that in Belarus the practice of overt surveillance is determined by the economical, rather than humanitarian considerations. There are simply not enough prisons and prison guards for everyone. If they did have enough, what moral principles would have prevented them from enclosing the entire country with barbed wire?

There is no limit

August protests of 2020 in Belarus were the result of many years of unchanged power, obvious falsification of the election, brazen lawlessness. Lawlessness, of course, is terrible, but somewhere deep inside we feel that even lawlessness should be limited by humaneness. A tyrant must stop when keeping absolute power means gutting the nation, this is what we think. But this is precisely the issue, throughout this entire story we have not encountered a single case where somebody powerful showed compassion and stopped.

Similarly, Russia's protests were primarily directed against corruption. Corruption is terrible, but again, somewhere deep inside we feel that it also should be limited by humaneness. Even a thief must stop stealing, even a brigand must stop robbing when their black craft turns into gutting the nation, this is what we think. But none of us can think of the time when corrupt officials followed at least this thieves’ rule: do not take from people the last thing they have left.

And so, while clearly less violent when compared with the 20th century, the current Belarusian repressions are less violent not because the hearts of the current tyrants softened. There is simply lack of money, executioners, and material tools of oppression, that’s all. There is no moral limit to cruelty.

Hanna L. was not released because the authorities felt bad for a musician in thick-rimmed glasses. Nastya B. was not released because they felt bad for a young, pretty cripple with higher education. Zhanna L. was not released because the elderly woman had diabetes. Olesya S. was not released because she was just visiting the country and had nothing to do with any of this in the first place. They were not released out of pity, humaneness, open-heartedness, not because the police had some limit to cruelty somewhere deep down in them that they would not exceed. The women were released because there were no means to finish them off completely.

All this is hard to believe. There has to be a heart somewhere deep under their armor. There must have remained some childhood fairy tales somewhere under those helmets and caps, mother’s lullabies, songs about kindness, fathers’ lessons to not hit girls, something! This is what the protesting Belarusian women in white dresses with flowers and sweets count on.

But the hearts of those serving the regime are silent. Physically current repressions are much weaker compared to the past century, but morally they do not differ at all. Flowers and white dresses are met with proud, self-aware cruelty. The only difference is that in the last century, it was the wolves that tore us apart on behalf of the state, and today it is the rats that do it.