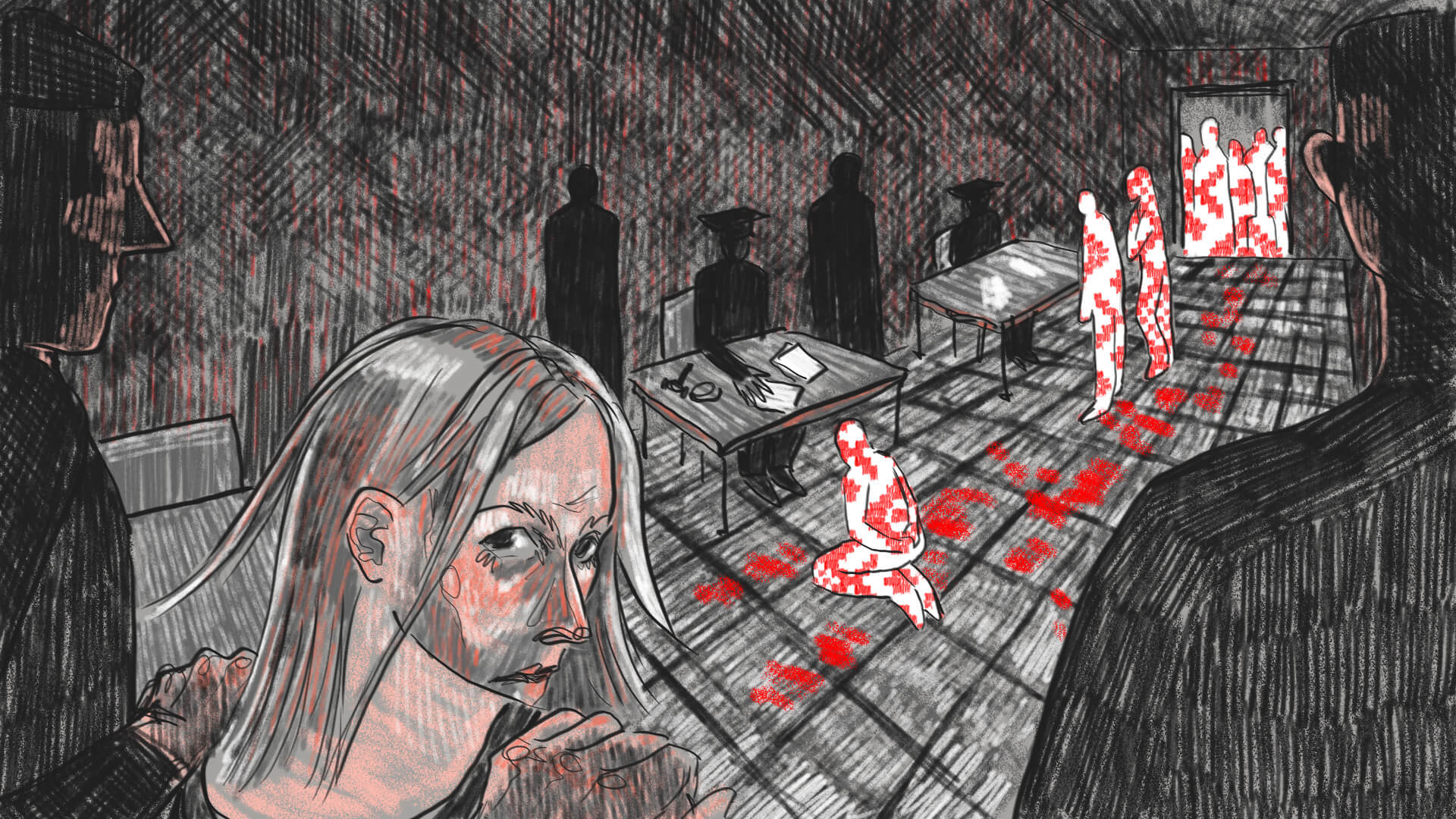

If Yulia G. were not told that she was going to court, she would not have realized that she was tried and sentenced.

- Come out, face the wall!

While convoy is busy with keys, Yulia looks out of the corner of her eye. And then looks some more as she is led to the courtroom. The corridors of the prison on Okrestina Street are full of people. Mostly men. All beaten. Many to a bloody pulp. Many half-naked or dressed in torn, bloodied rags. Some stripped down to their underwear. Some completely naked. There is blood on the floor. Soles stick to the ground as if you are walking on glue.

Yulia does not remember if she saw a man with a broken arm herself or if this is another inmate’s story stuck her memory. The man stood in front of the judge nursing his hand as the judge continued the process asking questions and demanding answers.

- He has a broken arm! Call him an ambulance!

- We’ll finish with the trial and call then. A couple of minutes.

Zhanna L. definitely remembers the man with a broken arm. She clearly recalls that she asked someone to call an ambulance for him and got a no. Perhaps it was a different man with a broken arm. Perhaps there were several of them.

They are tried right in prison hallways. Tables stand along the walls and judges sit behind them. Some even in robes. Judges in robes amid blood and stench with naked defendants in front of them.

But Yulia G. is led past them. Women, at least those sitting in cell #18, are not judged in the hallways. They are tried in offices. There is nothing in the room Yulia is brought to that indicates it is a courtroom. And the woman who is sitting behind a table there does not look like a judge: no robe, no gavel, no other signs. The woman asks:

- What were you doing?

Yulia describes what she was doing at the time of arrest: came to the polling station, saw riot police officers detaining an independent observer, tried to defend him and was taken to the van herself.

The woman says:

- You may return to your cell.

Yulia is taken away. The trial is over. A couple of hours later, a man - in civilian clothes this time- enters the cell and yells loudly:

- Yulia G.! 15 days of arrest!

That’s all. The judge did not consider any motions, did not listen to the defense lawyer, did not retire to the deliberation room, did not read out any verdict or ruling. "You may return to your cell", that’s all.

The only thing Yulia managed to find out after her release was that the judge worked in one of the district courts in Minsk. Though she also found out that there was another judge, from a different district court, who tried her for the same “offence” at almost the same time. Her second punishment was four days of detention. Which of these guilty verdicts served as the reason for Yulia’s five-day prison arrest is still not clear.

One term

Court sentences had almost no impact on the actual number of days in detention the inhabitants of cell #18 served.

Two separate trials sentenced Yulia G. to a total 19 days of arrest, but she served 5. This can be explained neither by the principle of combination, nor the absorption of terms.

Olesya S. was not tried at all, but this did not protect her from being kept in the cell for as long as it was necessary.

Zhanna L. was tried twice. Both times, of course, not for having asked to get in the van which her daughter was shoved into right in front of her eyes. Both times she was tried for allegedly protesting and shouting slogans in two separate parts of the city at the same time. Both times she was fined. And even then, she was not freed after the trial but taken back to the cell. The difference is that unlike her cellmates, she was there for four days, not five.

Zhanna's daughter Polina Z. was not given any sentence during the trial. An unknown policeman entered the cell at some point and announced: "Ten days." She served six.

Lena A. cried during the trial, partially admitted guilt and asked them not to punish her with arrest but give her a fine. Unlike others, Lena was tried not in prison but in a real court building. The trial was quick, though the judge did allow a couple of motions, and the convoy guard let her parents give her a care package. But neither motions nor tears helped. The judge Mister Prison Days (the nickname he got after August events) still sentenced her to twelve days in custody.

And Hanna L. cried. Not in hopes for compassion but out of the burning sense of injustice. She got six days. They say the 24 hours were for not signing the protocol.

Tanya P. did not cry. On the contrary, she was happy to get five days. She laughed that the court materials had her as Tamara, not Tatiana, and a different last name. It did not occur to her that her relatives on the outside were searching everywhere for her, that they considered her missing, could not find her in any police precinct or prison because the records said Tamara. She did think that (whether as Tatiana or Tamara) she would be freed by the weekend and manage to be at work on Monday. So, whether you repent or resist, ask for leniency or could not care less about it, it changes nothing.

Nastya B. had two trials. One sentenced her to ten days of arrest, the other twenty. She served five. Not a single lawyer in the world would be able to explain how this math works.

And Yulia Filipova saw that the judge wrote her sentence, eight days, with a pencil. It was at least neat. You never know what further instructions would come from above and this way it would be possible to erase things, fix something and the official paperwork would still be spotless.

Another woman

Olga Pavlova was not tried. That’s not true, there was a trial, but not of Olga. No, not exactly true either. Olga was tried, but instead of some other woman also called Olga Pavlova. Who was tried for this Olga Pavlova? No one really knows.

Olga was taken to the courtroom. The judge opened the documents. Clarified if it was Olga Pavlova in front of her. Received a yes. And then asked, looking right in the protocol: - Whose photograph is this?

Olga looked at the photo and answered briefly:

- No clue, not mine.

Then the judge began to ask questions.

Date of birth? Not the same as in the protocol.

Passport number? Doesn't match.

Home address? Not Olga’s in the protocol, someone else’s.

Father's name? Not the same.

Mother's name? Again, a mismatch.

- But you are Olga Pavlova? – finally asked the judge hoping that this misunderstanding would somehow resolve on its own.

- Olga Pavlova, admitted the defendant. - But not this one. Quite a common name.

The judge put down the case and started calling someone. Same clarifications were made in the phone conversation: father’s name, mother’s name, home address, passport number, nothing matched. The judge rolled her eyes and almost screamed at the phone:

- How am I supposed to do this trial? There is a different person in front of me.

But have no doubt, if it is not possible to try one person instead of another, it is still possible to put them her prison for somebody else. Not examining the case, the judge ordered the convoy to take Olga away. She was taken to the cell where she spent, like everybody else, five days that started her odyssey of detention centers and prisons.

Upon her release, wishing to challenge her detention Olga Pavlova demanded to see her case. After some effort this Olga Pavlova managed to obtain the case of the other Olga Pavlova. On top of the file, in a simple ballpoint pen someone wrote without any explanation: 15 days.