Tanya P.'s relationship with her father has always been difficult. Her father constantly pressured her, tried to control her life, told her who to befriend and who to avoid, what to study, where to work, whether to have pets. Tanya rebelled in response: she shaved her head, wore men's clothes, got tattoos, got a dog, a cat, another cat ...

On August 9th, Tanya put several bottles of hydrogen peroxide, painkillers, and bandages into her backpack. She clearly understood what she had to do during the protests - help the wounded. An undoubtedly noble and moral deed, so much so that even in large and bloody wars opposing sides try to protect nurses and medical assistants, even those on the other side.

But Tanya's father thought differently. He tried to stop her. He called and yelled at her that by participating in the protests, Tanya was endangering not only herself but also him, his career, his well-being, the well-being of the whole family. And it’s all pointless, after all! It is so stupid to risk your career and your normal, normal, admit it your completely normal life on the side of Polish and Lithuanian provocateurs. That is what he said, but Tanya did not listen. She was fed up with the paternal care both from her own dad and from the nation’s batska (father’ in the Belarusian language, it was used as a slang name for president Lukashenko) because you, the fathers, might not know just how unbearable your paternal care sometimes is.

Tanya noticed that authoritarian men, foaming at the mouth and with faces distorted by fury, often ramble on about some moralistic nonsense and don’t think clearly. Her dad raised his voice at Tanya but had no idea how to actually stop her. After her arrest the riot police in the prisoner transport vehicle didn’t just raise their voices, they bellowed like drill sergeants. They snatched her backpack away, they grabbed her phone, but they didn’t think to yank the Apple Watch off of her arm. An Apple Watch isn’t meant to send messages back and forth, but it’s still possible. And that’s what Tanya did - she sent a message to the one man who didn’t try to control her, a man she both respected and even feared a bit. She texted her boss and explained that she was detained and wasn’t sure when she’d be able to come back to work. Her boss replied, “Thanks for the warning. Good luck. I hope everything will work out".

Fathers of the world, you see, your daughters don’t feel better when you, choking on a cocktail of love, fear, and anger, yell at them: "What have you done with your life, you idiot!!" Your daughters feel better when you say, “Thank you for telling me. I hope everything will be ok". You can also make your daughters’ lives a little easier by simply offering to help, although as a general rule, fathers can’t do much to help outside of sending over some money. That’s how Tanya saw it anyway, and during her 5 days in prison she encountered authoritarian male moralizing dozens of times, but never even a hint of male compassion.

The head of the police station where Tanya was brought for processing wasn’t a bad man, he wasn’t evil. But his "words of support" came straight from Captain Obvious. "If you take part in the protests, you will be arrested." "If you resist, you will get beaten." It was like being told that if you have sex, you’ll get pregnant or that if you wear men’s clothes, you’ll never find a husband. The question isn’t whether or not you will be arrested if you protest - that’s self-evident. The question is how did you, men with strong hands and commanding voices, allow a girl to be arrested for walking down the street with two bottles of hydrogen peroxide in her backpack?

This particular police chief wasn’t an animal, he treated Tanya with a fatherly attitude and didn’t want to send Tanya and her friend to jail, fully aware that they would be tortured there. But he received an order, and so he took them to prison, excusing his obedience and groveling with the appropriate amount of moralizing.

Tanya met another not-evil man in prison. One of the escort officers. When it became unbearably stuffy in cell #18 (to the point of fainting), he took the prisoners out to breathe in the corridor. But Nastya B., having breathed in some actual oxygen for once, lost consciousness and fell to the floor. The jailer's humanitarian impulse was revealed when more escort officers and paramedics came running. That man immediately began to complain to the prisoners that now he’s going to be in hot water with the higher ups.

Is this the stronger sex? Complaining to battered, unwashed, hungry, fainting women that you’re going to be written up? Seriously? Tanya realized that men, as a rule, are surprisingly weak creatures. And firmly decided to get a new tattoo as soon as she gets released.

Of course,Tanya had a hard time in the cell. But she admired the women locked up with her. Olga Pavlova (Tanya calls her the face of the protests) slowly unscrewed the prison with a nail file right in front of Tanya’s eyes. Novels like The Count of Monte Cristo are written and movies like Shawshank Redemption are made about people who unscrew prisons.

Zhanna L., who was herself suffering from diabetic nausea, found the strength to comfort Yulia G. through the panic attack that gripped her. Olesya S. actively defended her rights and laughed at her tormentors. Nastya B. - the heart and soul of the group! - somehow found a fork, washed her hair with the rusty tap water, and combed her hair with the fork so as to not succumb to the stench and dirt of the prison. Tanya admired them. She thought that for some reason, repression breaks men with strong hands and commanding voices easier than women. And somehow that observation was tied with her desire to get a new tattoo.

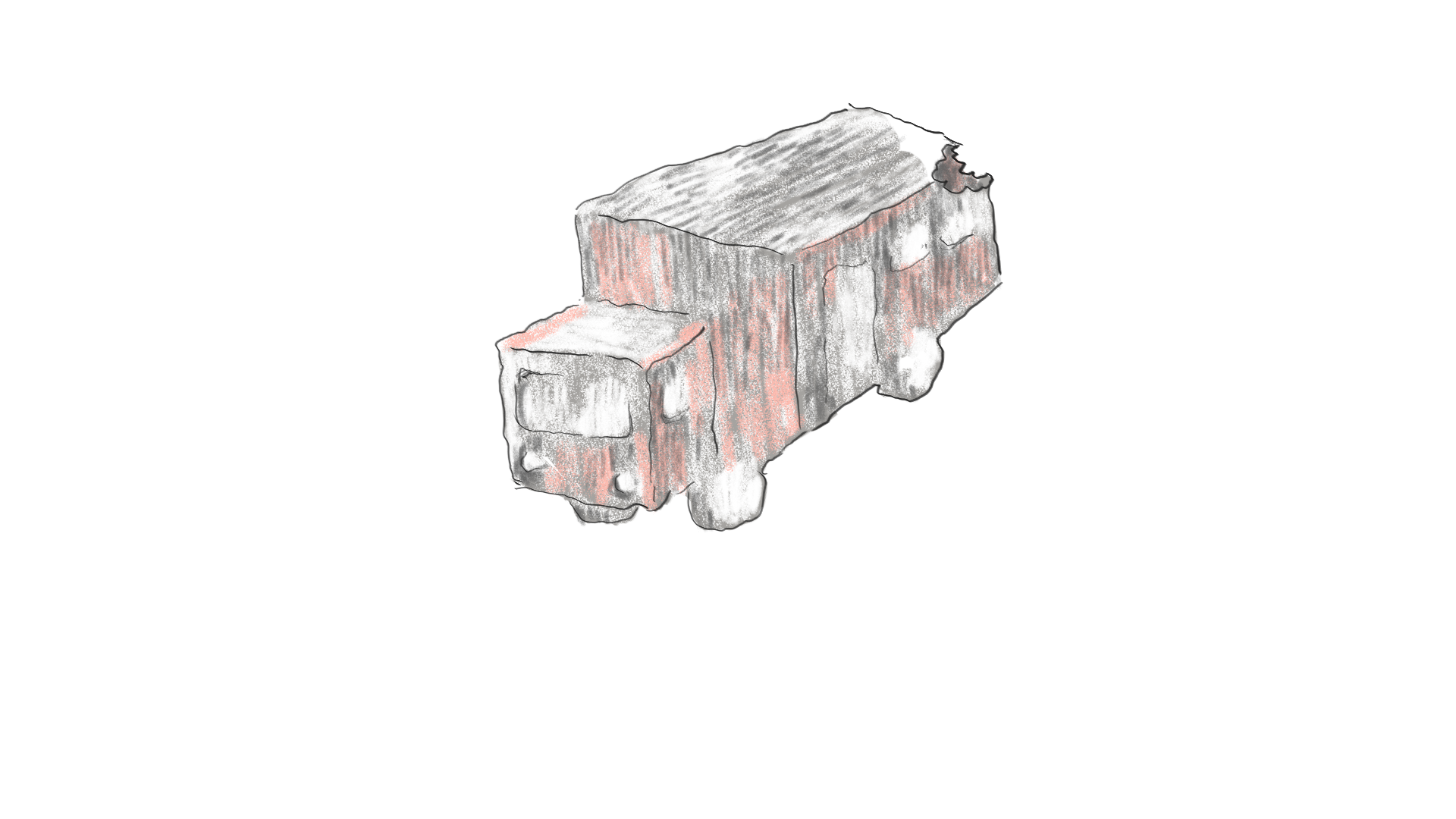

In Zhodino, Tanya made a police van out of bread shortly before her release to entertain her friends. It turned out pretty good. The group had fun. The model police van was eaten.

Walking out of the prison gates, in the rays of numerous flashlights and camera flashes, Tanya saw her father. He was crying. Bitterly, powerlessly, like a lost child.